워렌 버핏 주주서한, 왜 주식투자가 금이나 채권보다 더 나은 투자인가

2015. 9. 6. 13:36 - the thinker

제 투자 철학은 워렌 버핏의 가치투자 철학과 동일합니다. 특히 인플레이션의 장기 영향으로부터 어떤 태도를 취해야 할지에 대해서 워렌 버핏의 주주서한이 주는 통찰력은 깊이 동감하고 있습니다. 아래에 주주서한을 첨부합니다. 한글로 해석해 주신 블로그가 있어서 옮겨봅니다. 한글 버전은 선암님 블로그 에서 옮겨왔습니다.

Warren Buffett: Why stocks beat gold and bonds

워런 버핏: 왜 주식투자가 금이나 채권보다 더 나은 투자인가

FORTUNE -- Investing is often described as the process of laying out money now in the expectation of receiving more money in the future. At Berkshire Hathaway (BRKA) we take a more demanding approach, defining investing as the transfer to others of purchasing power now with the reasoned expectation of receiving more purchasing power -- after taxes have been paid on nominal gains -- in the future. More succinctly, investing is forgoing consumption now in order to have the ability to consume more at a later date.

일반적으로 투자라는 개념은 미래에 더 많은 돈을 받기 위해 지금 현재 자금을 자산에 투입하는 과정으로 알려져 있습니다. 저희 버크셔해서웨이에서는 조금 더 까다로운 기준으로 투자의 개념을 정의합니다. 저희 생각에, 투자라고 하는 것은 미래에 더 많은 구매력(명목 이윤에서 세금을 제한 후의 구매력)을 가지기 위해 현재 소유한 구매력을 타인에게 양도하는 행위입니다. 즉, 투자라는 것은 미래에 더 많은 소비를 하기 위해 현재 소비를 줄이는 것 입니다.

From our definition there flows an important corollary: The riskiness of an investment is not measured by beta (a Wall Street term encompassing volatility and often used in measuring risk) but rather by the probability -- the reasoned probability -- of that investment causing its owner a loss of purchasing power over his contemplated holding period. Assets can fluctuate greatly in price and not be risky as long as they are reasonably certain to deliver increased purchasing power over their holding period. And as we will see, a nonfluctuating asset can be laden with risk.

Investment possibilities are both many and varied. There are three major categories, however, and it's important to understand the characteristics of each. So let's survey the field.

저희가 내린 투자의 정의에는 중요한 시사점이 내포되어 있습니다. 그 시사점은 바로, 투자에 대한 리스크의 척도는 자산의 베타 (월가에서 자산의 변동성을 이용해 리스크를 측정하는 수치) 가 아니라, 그 자산을 가진 소유자가 해당 자산을 보유할 기간 동안 구매력을 상실하게 되는 확률(합리적인 확률)이라는 것입니다. 어느 한 자산이 보유 기간 동안 구매력이 증가될 것이 확실하다는 것을 합리적으로 예측할 수 있다면 자산가격이 위아래로 심하게 요동한다고 하더라도 리스크가 거의 없는 것으로 간주할 수 있으며, 또 그 반대로, 제가 뒤에서 더 자세히 다루겠지만, 거의 변동성이 없는 자산이 오히려 매우 큰 리스크를 가진 자산일수도 있습니다. 투자 가능한 자산의 종류들은 많고 다양하지만, 모든 범주를 통틀어서 크게 세 가지로 나눌 수 있습니다. 이 세 가지 투자처의 차이점을 이해하는 것은 매우 중요하기 때문에 하나씩 살펴보도록 하겠습니다.

Investments that are denominated in a given currency include money-market funds, bonds, mortgages, bank deposits, and other instruments. Most of these currency-based investments are thought of as "safe." In truth they are among the most dangerous of assets. Their beta may be zero, but their risk is huge.

첫 번째 종류의 투자처는 단기금융자산투자신탁(Money-market fund, MMF), 채권, 모기지, 은행 예금 등 현금의 성질을 띄며 기존 화폐로 표기된 투자입니다. 이러한 종류의 투자는 매우 “안전”하다고 여겨지지만, 실제로 이 자산들은 가장 위험성이 높은 투자처 중 하나입니다. 이 자산들의 베타는 0에 가까울지 몰라도 그 리스크는 매우 큰 것입니다.

Over the past century these instruments have destroyed the purchasing power of investors in many countries, even as these holders continued to receive timely payments of interest and principal. This ugly result, moreover, will forever recur. Governments determine the ultimate value of money, and systemic forces will sometimes cause them to gravitate to policies that produce inflation. From time to time such policies spin out of control.

제 때에 이자를 지급하고 원금을 상환했던 투자도구들이지만, 지난 한 세기 동안 이러한 자산들은 수 많은 투자자들의 구매력을 잠식시켰습니다. 더 안타까운 것은 이러한 추세가 영원히 계속될 것이라는 사실 입니다. 궁극적인 화폐의 가치는 정부가 결정하게 되고, 주기적으로 발생하는 거시적인 요인들로 인해 정책입안가들은 통화팽창에 의지하게 되며 이따금 그런 정책들은 통제불가능 상태로 치닫기도 합니다.

Even in the U.S., where the wish for a stable currency is strong, the dollar has fallen a staggering 86% in value since 1965, when I took over management of Berkshire. It takes no less than $7 today to buy what $1 did at that time. Consequently, a tax-free institution would have needed 4.3% interest annually from bond investments over that period to simply maintain its purchasing power. Its managers would have been kidding themselves if they thought of any portion of that interest as "income."

안정된 화폐로써의 위치가 굳건해야 하는 미국에서조차 달러의 가치는 1965년부터 지금까지 86%나 부식되었습니다. 1965년은 제가 버크셔해서웨이의 경영을 시작할 때였는데, 그때 1달러로 살 수 있었던 물건은 지금 최소한 7달러는 줘야 살 수 있습니다. 그렇기 때문에, 세금이 면제되는 투자 기관은 채권투자에 대해 연 4.3%의 이자를 받았어야만 투자자금에 대한 구매력을 겨우 유지할 수 있었을 것입니다. 해당 기관의 투자담당자가 그 부분의 이자를 “수익”이라고 주장하는 것은 어불성설입니다.

For taxpaying investors like you and me, the picture has been far worse. During the same 47-year period, continuous rolling of U.S. Treasury bills produced 5.7% annually. That sounds satisfactory. But if an individual investor paid personal income taxes at a rate averaging 25%, this 5.7% return would have yielded nothing in the way of real income. This investor's visible income tax would have stripped him of 1.4 points of the stated yield, and the invisible inflation tax would have devoured the remaining 4.3 points. It's noteworthy that the implicit inflation "tax" was more than triple the explicit income tax that our investor probably thought of as his main burden. "In God We Trust" may be imprinted on our currency, but the hand that activates our government's printing press has been all too human.

여러분과 저 같이 세금을 내야 하는 투자자들에게는 상황이 더욱 좋지 않습니다. 같은 47년의 기간 동안, 미국 채권은 연 평균 5.7%의 수익률을 기록했습니다. 얼핏 듣기에는 만족할 만한 수치 같지만, 평균 25%의 세율을 적용한다면 5.7%의 수익률을 올린 투자자는 실제 소득이 전혀 없는 것과 같습니다. 눈에 보이는 소득세로 인해 1.4%의 수익을 세금으로 납부해야 되는 투자자는 나머지 4.3%의 수익을 보이지 않는 인플레이션 세금으로 전부 납부해버릴 것이기 때문입니다. 일반적으로 투자자들이 가장 짐스럽게 생각하는 세금이 보이지 않는 인플레이션 “세금”의 1/3에 불과 하다는 사실은 주목할 만 한 사실입니다. “우리는 하느님을 믿는다(In God We Trust)”라는 문구와 상반되게, 정부의 인쇄소는 우리 인간에 의해 가동되고 있었습니다.

High interest rates, of course, can compensate purchasers for the inflation risk they face with currency-based investments -- and indeed, rates in the early 1980s did that job nicely. Current rates, however, do not come close to offsetting the purchasing-power risk that investors assume. Right now bonds should come with a warning label.

1980년대에 그랬듯이, 화폐성 투자 자산이 제공하는 높은 이자율은 구매자들이 직면한 인플레이션 리스크를 충분히 상쇄할 수도 있습니다. 하지만 현재 시장 금리는 투자자들을 위협하는 구매력 감소의 리스크에 비하면 너무나도 낮은 수준에 머무르고 있습니다. 현 시점에 채권을 구매하는 것은 매우 신중해야 할 것 입니다.

Under today's conditions, therefore, I do not like currency-based investments. Even so, Berkshire holds significant amounts of them, primarily of the short-term variety. At Berkshire the need for ample liquidity occupies center stage and will never be slighted, however inadequate rates may be. Accommodating this need, we primarily hold U.S. Treasury bills, the only investment that can be counted on for liquidity under the most chaotic of economic conditions. Our working level for liquidity is $20 billion; $10 billion is our absolute minimum.

그렇기 때문에 저는 지금과 같은 상황에서는 화폐성 자산에 투자하는 것이 옳지 않다고 생각하고 있습니다. 시장금리 상황이 이 같이 불리하지만, 버크셔해서웨이는 풍부한 유동성을 보유하기 위해 만기가 단기인 자산을 위주로 한 화폐성 자산을 일부 보유하고 있습니다. 시장금리가 어떻든 간에 유동성을 유지하는 것의 중요성은 아무리 강조해도 지나치지 않습니다. 저희는 가장 혹독한 경제 상황에서도 유동성을 유지할 수 있는 유일한 자산인 미국 국채를 위주로 유동성 관리를 하고 있습니다. 버크샤이어에서 유지하려고 하는 유동성의 양은 2백억 달러 이며, 절대적인 최소 한도는 1백억 달러입니다.

Beyond the requirements that liquidity and regulators impose on us, we will purchase currency-related securities only if they offer the possibility of unusual gain -- either because a particular credit is mispriced, as can occur in periodic junk-bond debacles, or because rates rise to a level that offers the possibility of realizing substantial capital gains on high-grade bonds when rates fall. Though we've exploited both opportunities in the past -- and may do so again -- we are now 180 degrees removed from such prospects. Today, a wry comment that Wall Streeter Shelby Cullom Davis made long ago seems apt: "Bonds promoted as offering risk-free returns are now priced to deliver return-free risk."

저희는 지속적으로 유동성 관리를 위해 화폐성 자산을 이용하지만, 금리가 높은 수준으로 올라가 국채가격의 상승여지가 존재하거나 정크본드가 폭락해 저평가된 채권이 시장에 나오는 등의 보기 드문 투자기회가 포착된다면 화폐성 자산에도 때때로 투자하고 있습니다. 저희는 과거에 그런 투자기회들을 이용했었지만(그리고 앞으로도 그렇게 하겠지만), 현재로써는 그런 자산에 대한 투자를 전혀 하지 않고 있습니다. 지금 시장 상황은 월가의 셀비 컬롬 데이비스가 오래전에 했던 말이 잘 설명해주고 있는 것 같습니다: “무 위험 수익을 올려준다고 추앙 받던 채권자산의 가격이 너무 오른 나머지, 이제는 무 수익 위험을 가져다 주는 자산으로 전락해 버렸다.”

The second major category of investments involves assets that will never produce anything, but that are purchased in the buyer's hope that someone else -- who also knows that the assets will be forever unproductive -- will pay more for them in the future. Tulips, of all things, briefly became a favorite of such buyers in the 17th century.

제가 이 서한에서 언급할 두 번째 종류의 투자처는 실질적으로 창출되는 가치는 아무것도 없지만 누군가에게 더 비싼 값에 팔 수 있을 것이라는 희망을 안고 구입하는 투자자산입니다(투자자들 모두 이 자산으로 인해 창출되는 가치가 전혀 것도 없다는 것을 정확히 알고 있습니다). 17세기에는 튤립이 잠시 동안 이런 투자자들에게 선풍적인 인기를 끌었었죠.

This type of investment requires an expanding pool of buyers, who, in turn, are enticed because they believe the buying pool will expand still further. Owners are not inspired by what the asset itself can produce -- it will remain lifeless forever -- but rather by the belief that others will desire it even more avidly in the future.

이런 종류의 투자는 보통 구매자들의 숫자가 갈수록 늘어가야만 그 구매력이 유지되거나 증가될 수 있습니다. 그리고 새로운 구매자들은 투자한 자산에서 발생하는 실질 가치보다는(이런 투자에서는 실질가치가 영원히 발생하지 않습니다) 앞으로 더욱더 많은 사람이 그 자산을 구매할 것이라는 믿음을 가지고 투자하게 됩니다.

The major asset in this category is gold, currently a huge favorite of investors who fear almost all other assets, especially paper money (of whose value, as noted, they are right to be fearful). Gold, however, has two significant shortcomings, being neither of much use nor procreative. True, gold has some industrial and decorative utility, but the demand for these purposes is both limited and incapable of soaking up new production. Meanwhile, if you own one ounce of gold for an eternity, you will still own one ounce at its end.

두 번째 종류에 속하는 투자 자산에 속하는 대표적인 예로 금을 들 수 있겠습니다. 금을 제외한 거의 모든 자산을 소유하는 것을 두려워하는 투자자들에게, 그 중에서도 특히나 화폐성 자산을 소유하는 것을 두려워하는 투자자들에게(그리고 앞에서 언급했듯이 화폐성 자산은 충분히 두려워할 만한 이유가 있습니다) 금은 매우 인기 있는 투자처입니다. 하지만 금은 두 가지 치명적인 결함이 있는 자산입니다. 첫째로 그다지 쓸모가 있는 물건이 아니며, 둘째로는 물리적으로 불어나는 자산이 아니라는 점입니다. 물론 금이 공업용도로 쓰이기도 하고 장식용으로도 쓰이지만, 이러한 용도는 매우 한정적인데다 새로운 생산을 촉진하지도 못합니다. 평생 동안 금을 1 온스 가지고 있다면 나중에도 남는 건 결국 금 1 온스 입니다.

What motivates most gold purchasers is their belief that the ranks of the fearful will grow. During the past decade that belief has proved correct. Beyond that, the rising price has on its own generated additional buying enthusiasm, attracting purchasers who see the rise as validating an investment thesis. As "bandwagon" investors join any party, they create their own truth -- for a while.

금 투자자들을 움직이는 힘은 바로 시장의 공포심이 갈수록 증가될 것이라는 믿음입니다. 지난 10년 동안 그런 믿음은 옳았다는 사실이 입증되었고, 치솟는 가격은 더 많은 사람들의 구매를 부추겼습니다. “밴드왜건” 투자자들이 파티에 참가하면서 얼마 동안은 그들 자신만의 진리를 만들어가게 됩니다.

Over the past 15 years, both Internet stocks and houses have demonstrated the extraordinary excesses that can be created by combining an initially sensible thesis with well-publicized rising prices. In these bubbles, an army of originally skeptical investors succumbed to the "proof " delivered by the market, and the pool of buyers -- for a time -- expanded sufficiently to keep the bandwagon rolling. But bubbles blown large enough inevitably pop. And then the old proverb is confirmed once again: "What the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end."

처음에 그럴듯해 보였던 투자적 근거와 대중에게 잘 알려진 상승 랠리가 어우러져 인터넷 관련 주식과 주택시장은 지난 15년 동안 놀라운 성장을 보였습니다. 본래 의구심을 가지고 지켜보던 많은 투자자들은 시장의 “증거”에 굴복하였고, 투자자의 수는 일정한 기간 동안 꾸준히 늘어만 가면서 그 랠리를 유지했습니다. 하지만 크게 부풀려진 버블은 터지기 마련입니다. 옛 격언이 옳다는 것이 다시 한번 입증되었습니다: “현명한 사람이 처음에 하던 것을 결국 맨 끝에 가서 바보가 따라 한다.”

Today the world's gold stock is about 170,000 metric tons. If all of this gold were melded together, it would form a cube of about 68 feet per side. (Picture it fitting comfortably within a baseball infield.) At $1,750 per ounce -- gold's price as I write this -- its value would be about $9.6 trillion. Call this cube pile A.

현재 전 세계에 있는 금의 비축양은 17만 미터 톤 입니다. 세상에 모든 금을 다 녹여서 한 덩어리로 만든다면 한 변이 20.7미터 정도 되는 정육면체가 될 것입니다(야구장에 있는 내야 필드를 조금 여유를 남기고 채우는 정도의 크기로 생각하시면 됩니다). 1 온스당 1750달러(제가 이 서한을 쓰는 시점의 금 값입니다)로 계산한다면, 그 정육면체의 금 덩어리 값은 9조 6천억 달러가 됩니다. 일단 이 금 덩어리를 A라고 하겠습니다.

Let's now create a pile B costing an equal amount. For that, we could buy all U.S. cropland (400 million acres with output of about $200 billion annually), plus 16 Exxon Mobils (the world's most profitable company, one earning more than $40 billion annually). After these purchases, we would have about $1 trillion left over for walking-around money (no sense feeling strapped after this buying binge). Can you imagine an investor with $9.6 trillion selecting pile A over pile B?

이제 같은 값어치가 나가는 B를 생각해보도록 하겠습니다. 그 돈으로 우리는 미국의 모든 경작지(4천억 에이커의 면적, 매년 산출량 2천억 달러 이상)와 16개의 엑손 모빌회사(세계에서 가장 수익성이 좋은 기업, 매년 4백억 달러 수익)을 살 수 있습니다. 이렇게 구매를 한 후에도 1조 달러 가량의 용돈이 남습니다(많이 지출하긴 했지만 이 정도나 남았으니 죄책감 가질 필요는 없겠죠). 과연 어떤 투자자가 과연 B를 마다하고 A를 선택할까요?

Beyond the staggering valuation given the existing stock of gold, current prices make today's annual production of gold command about $160 billion. Buyers -- whether jewelry and industrial users, frightened individuals, or speculators -- must continually absorb this additional supply to merely maintain an equilibrium at present prices.

이와 같은 금의 충격적인 밸류에이션을 뒤로 하고서라도 매년 1600억 달러에 달하는 금이 새로 채굴되고 있습니다. 보석상, 공업자, 두려움에 떠는 개인 투자자 및 투기꾼을 포함한 구매자들은 지속적으로 이 가격에 나오는 금을 온전히 받아들여야지만 현재 가격이 겨우 균형을 유지할 수 있을 것입니다.

A century from now the 400 million acres of farmland will have produced staggering amounts of corn, wheat, cotton, and other crops -- and will continue to produce that valuable bounty, whatever the currency may be. Exxon Mobil (XOM) will probably have delivered trillions of dollars in dividends to its owners and will also hold assets worth many more trillions (and, remember, you get 16 Exxons). The 170,000 tons of gold will be unchanged in size and still incapable of producing anything. You can fondle the cube, but it will not respond.

앞으로 1세기가 지나면 4천억 에이커의 농작지에서 엄청난 양의 옥수수, 밀, 면직물 같은 작물이 생산될 것이며, 1세기가 지난 후에도 이와 같은 경작물은 계속 생산됩니다. 엑손모빌은 아마도 몇 조 달러에 해당하는 막대한 금액을 주주들에게 배당으로 나눠주고 그 자산가치의 상승으로 인해 투자자들에게 수 조 달러를 더 안겨줄 것입니다. 그에 반해 17만 톤의 금 덩어리는 부피도 변하지 않을뿐더러 아무것도 생산해 내지 못할 것입니다. 금 덩어리를 아무리 쓰다듬어줘도 변하는 건 없을 것입니다.

Admittedly, when people a century from now are fearful, it's likely many will still rush to gold. I'm confident, however, that the $9.6 trillion current valuation of pile A will compound over the century at a rate far inferior to that achieved by pile B.

물론, 만약 지금으로부터 1세기가 지난 후에도 대중이 투자자산들에 대한 두려움을 갖게 된다면 금에 대한 수요는 높을 수 있습니다. 하지만 저는 복리로 계산된 9조 6천억 달러짜리 금 덩어리 A의 100년 수익률은 절대 B를 따라 잡을 수 없다고 확신합니다.

Our first two categories enjoy maximum popularity at peaks of fear: Terror over economic collapse drives individuals to currency-based assets, most particularly U.S. obligations, and fear of currency collapse fosters movement to sterile assets such as gold. We heard "cash is king" in late 2008, just when cash should have been deployed rather than held. Similarly, we heard "cash is trash" in the early 1980s just when fixed-dollar investments were at their most attractive level in memory. On those occasions, investors who required a supportive crowd paid dearly for that comfort.

저희가 앞서 분류한 두 가지 종류의 투자는 두려움이 만연한 시기에 가장 인기를 누립니다. 경제시스템과 화폐의 붕괴에 대한 두려움이 개인 투자자들을 미국 국채 같은 화폐성 자산이나 금 같은 실물화폐로 이끌었습니다. 현금을 가지고 있기 보다는 써야 했던 2008년에 “현금이 왕이다”라는 표현이 나돌았고, 채권 투자가 가장 매력적인 시기였던 1980에 오히려 “현금은 쓰레기다”라는 말을 들을 수 있었습니다. 그와 같은 말을 하던 투자자들은 대중과 시장의 지지를 얻지 못하고 뼈아픈 대가를 치러야 했습니다.

My own preference -- and you knew this was coming -- is our third category: investment in productive assets, whether businesses, farms, or real estate. Ideally, these assets should have the ability in inflationary times to deliver output that will retain its purchasing-power value while requiring a minimum of new capital investment. Farms, real estate, and many businesses such as Coca-Cola (KO), IBM (IBM), and our own See's Candy meet that double-barreled test. Certain other companies -- think of our regulated utilities, for example -- fail it because inflation places heavy capital requirements on them. To earn more, their owners must invest more. Even so, these investments will remain superior to nonproductive or currency-based assets.

여기까지 읽으시면서 예상하셨겠지만, 제가 개인적으로 가장 선호하는 투자처는 이제 언급할 세 번째 종류의 투자자산, 즉 기업, 농장 및 부동산을 포함한 생산성을 가진 자산입니다. 원칙적으로, 이 부류의 자산들은 최소한도의 자금 투자만 있으면 물가상승의 시기에도 구매력을 유지할 수 있는 여력을 갖추고 있습니다. 농장, 부동산, 그리고 코카콜라나 IBM같은 기업들은 (저희 회사가 투자한 See’s Candy까지도) 그 투자조건에 부합합니다. 정부에 의해 규제를 받는 전력회사 같은 기업들은 그 기준에 달하지 못하는데, 그것은 그 기업들의 특성상 인플레이션보다 높은 수익을 거두기 위해 거액의 투자를 필요로 하기 때문입니다. 더 벌고자 하면 그 기업의 경영자들은 반드시 더 투자해야 합니다. 그래도 이런 기업들에 대한 투자는 아무 가치도 만들어 낼 수 없는 자산에 대한 투자나 화폐성 자산보다는 더 좋은 투자입니다.

Whether the currency a century from now is based on gold, seashells, shark teeth, or a piece of paper (as today), people will be willing to exchange a couple of minutes of their daily labor for a Coca-Cola or some See's peanut brittle. In the future the U.S. population will move more goods, consume more food, and require more living space than it does now. People will forever exchange what they produce for what others produce.

지금부터 1세기가 지난 후에 쓰일 화폐가 금이든 조가비이든 상어이빨이든 아니면 지금 우리가 쓰는 종이든 간에, 사람들은 변함 없이 몇 분의 노동과 코카콜라를(혹은 See’s Candy의 땅콩 캬라멜을) 맞바꾸려고 할 것입니다. 미래에는 미국 사람들이 지금 보다 더 많은 제품과 상품을 주고 받고, 더 많은 음식을 섭취하고, 더 넓은 거주공간을 필요로 할 것입니다. 사람들은 언제나 타인이 생산한 것을 자신이 생산한 것과 교환할 것입니다.

Our country's businesses will continue to efficiently deliver goods and services wanted by our citizens. Metaphorically, these commercial "cows" will live for centuries and give ever greater quantities of "milk" to boot. Their value will be determined not by the medium of exchange but rather by their capacity to deliver milk. Proceeds from the sale of the milk will compound for the owners of the cows, just as they did during the 20th century when the Dow increased from 66 to 11,497 (and paid loads of dividends as well).

우리나라의 기업들은 변함없이 우리 시민들에게 효율적으로 상품과 서비스를 제공할 것입니다. 비유적으로 이야기 하자면, 이런 상업적 “젖소”들은 앞으로도 몇 세기를 걸쳐 더 많은 양의 “우유”를 산출할 것입니다. 이 젖소들의 가치는 교환매개로써가 아닌 우유를 공급하는 능력에 의해 결정됩니다. 20세기 동안 다우존스지수가 66에서 11,497까지 상승한 것과 같이(많은 배당도 지급했었습니다) 우유를 팔아 생기는 수익은 젖소 소유자의 부를 축적시킬 것입니다.

Berkshire's goal will be to increase its ownership of first-class businesses. Our first choice will be to own them in their entirety -- but we will also be owners by way of holding sizable amounts of marketable stocks. I believe that over any extended period of time this category of investing will prove to be the runaway winner among the three we've examined. More important, it will be by far the safest.

버크셔해서웨이의 목표는 일류 기업들에 대한 지분을 늘리는 것입니다. 저희는 일반적으로 온전한 소유권을 가지려고 하겠지만, 상당한 양의 보통주 소유를 통해서 부분 지분을 소유 함으로써도 그렇게 할 것입니다. 어떤 기간 내에서 비교를 하든 간에, 저는 이 세 번째 종류의 투자가 나머지 두 가지 투자에 비해 월등히 우월한 투자전략이라 생각합니다. 더 중요한 점은, 이 방법이 무엇보다 가장 안전한 투자전략이라는 것입니다.

'투자아이디어' 카테고리의 다른 글

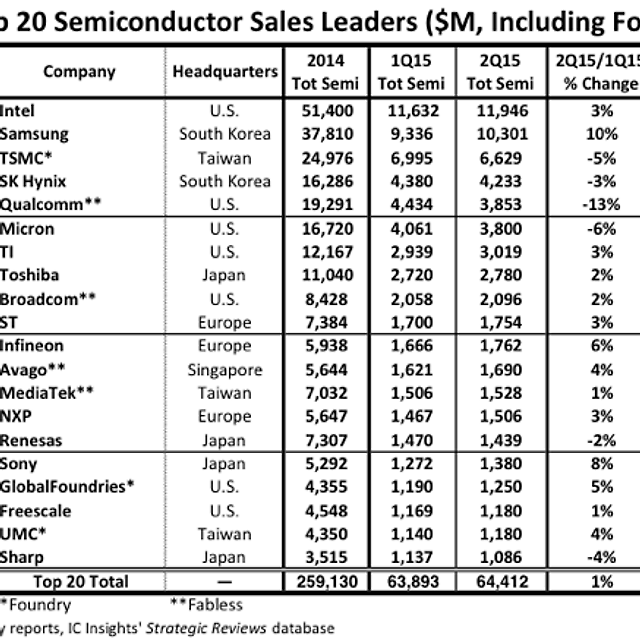

| 삼성전자를 LG전자보다 좋게 보는 이유, 전세계 반도체 매출액 추이 (0) | 2015.09.12 |

|---|---|

| 돈 약트먼 강연, 주식을 채권처럼 보라. (2) | 2015.09.08 |

| 지수 추종 ETF의 맹점 (0) | 2015.09.06 |

| Economic Korean 블로그 구독하기 (0) | 2015.09.04 |

| 대한방직 전주공장부지 매각 불발시 진입 아이디어 (0) | 2015.09.03 |